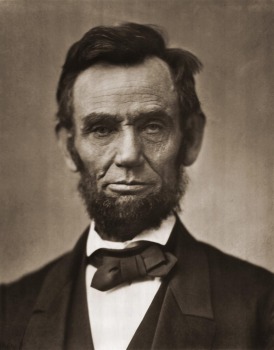

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) is widely regarded as one of the preeminent Presidents of the United States of America.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) is widely regarded as one of the preeminent Presidents of the United States of America.

Lincoln was opposed to the horrid and dehumanizing institution of slavery. However, rather than being one of the radicals within the Republican Party who advocated the immediate abolition of slavery across the entire country, he promoted a more moderate view. At the time, the opposing political group in Congress was the Democratic Party, which was dominated by a pro-slavery mindset, especially from its membership in the southern states.

Realising the economic realities of the southern states, and being respectful of their constitutional rights, Lincoln did not seek to extinguish the practice of slavery throughout the entire United States of America, but instead sought to stop it spreading, especially into the new US territories. He believed that slavery would eventually be ended across the whole country, but was willing to bide his time and let it be ended by popular vote, one state at a time.

He recognized that not only it would be difficult for the southern states to give up their slaves, but also that the emergence of so many freed slaves could be problematic for White American society, and so he suggested sending them to another country, such as Liberia in Africa.

Whilst he was opposed to slavery, Lincoln did not believe in granting Black Americans full equality with White Americans. In a speech he gave in 1854, at Peoria, Illinois, he said:

“When southern people tell us they are no more responsible for the origin of slavery, than we; I acknowledge the fact. When it is said that the institution exists; and that it is very difficult to get rid of it, in any satisfactory way, I can understand and appreciate the saying. I surely will not blame them for not doing what I should not know how to do myself. If all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do, as to the existing institution. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia, — to their own native land. But a moment’s reflection would convince me, that whatever of high hope, (as I think there is) there may be in this, in the long run, its sudden execution is impossible. If they were all landed there in a day, they would all perish in the next ten days; and there are not surplus shipping and surplus money enough in the world to carry them there in many times ten days. What then? Free them all, and keep them among us as underlings? Is it quite certain that this betters their condition? I think I would not hold one in slavery, at any rate; yet the point is not clear enough for me to denounce people upon. What next? Free them, and make them politically and socially, our equals? My own feelings will not admit of this; and if mine would, we well know that those of the great mass of white people will not. Whether this feeling accords with justice and sound judgment, is not the sole question, if indeed, it is any part of it. A universal feeling, whether well or ill-founded, can not be safely disregarded. We can not, then, make them equals. It does seem to me that systems of gradual emancipation might be adopted; but for their tardiness in this, I will not undertake to judge our brethren of the south.”1

Lincoln further expressed his views against granting Black Americans full equality with White Americans during a debate with Stephen A. Douglas in 1858:

“I will say then that I am not, or ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races — that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.”2

However, the secession of the southern states, and their creation of a new American nation, the Confederate States of America, changed the situation. Lincoln was willing to let slavery be ended on a piecemeal basis, but he was not willing for the USA to be split in two. The dividing of the USA into two separate nations led to the events which sparked the American Civil War (1861-1865), also known as the War Between the States.3 Whilst the beginnings of the armed conflict were quite complex4, anyone who says that the war was fought over the issue of slavery is grossly over-simplifying the matter.

In his first State of the Union address, in December 1861, Lincoln proposed creating a colony of American Blacks. He spoke about what to do with those Blacks who had been liberated from their Confederate owners by federal law, as well as those who may be liberated by the few slave-owing northern states:

“I recommend that Congress provide for accepting such persons from such States, according to some mode of valuation, in lieu, pro tanto, of direct taxes, or upon some other plan to be agreed on with such States respectively; that such persons, on such acceptance by the General Government, be at once deemed free; and that, in any event, steps be taken for colonizing both classes (or the one first mentioned, if the other shall not be brought into existence) at some place or places in a climate congenial to them. It might be well to consider, too, whether the free colored people already in the United States could not, so far as individuals may desire, be included in such colonization. . . . If it be said that the only legitimate object of acquiring territory is to furnish homes for white men, this measure effects that object, for the emigration of colored men leaves additional room for white men remaining or coming here.”5

In a letter, written in 1862 to Horace Greeley (editor of the New York Tribune), Lincoln stated that he did not go to war over the issue of slavery, but rather did so in order to save the Union (i.e. the United States of America):

“I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored, the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.”6

Lincoln took the opportunity afforded by the war to issue his Emancipation Proclamation, which (broadly speaking) ended slavery in the southern states, and thus he became known as the “great emancipator”.

As the freeing of so many slaves had the potential to cause great social conflict within America, Lincoln pursued his idea of sending Black Americans to another country, so as to avoid racial problems within the United States. Liberia, a colony in Africa for freed slaves, had already been established, and Lincoln had proposed that Blacks could be sent there; although he later proposed sending them to a colony in South America. He promoted his views amongst both Blacks and Whites.

One account is given of a meeting Lincoln had with some Black leaders, in 1862, to discuss the idea:

“You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any other two races. Whether it is right or wrong I need not discuss; but this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think. Your race suffer very greatly, many of them by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence. In a word we suffer on each side. If this is admitted, it affords a reason, at least, why we should be separated. . . . But for your race among us there could not be war, although many men engaged on either side do not care for you one way or the other. Nevertheless, I repeat, without the institution of slavery, and the colored race as a basis, the war could not have an existence. It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated. . . . The place I am thinking about having for a colony is in Central America. It is nearer to us than Liberia . . . The practical thing I want to ascertain is, whether I can get a number of able-bodied men, with their wives and children, who are willing to go when I present evidence of encouragement and protection. . . . I ask you, then, to consider seriously, not pertaining to yourselves merely, nor for your race and ours for the present time, but as one of the things, if successfully managed, for the good of mankind”.7

However, before Lincoln could put his plan into action, he was assassinated.

See also:

Abraham Lincoln advocates freeing the slaves and sending them to Africa, 16 October 1854

Abraham Lincoln speaks out against racial equality, 18 September 1858

Abraham Lincoln’s first State of the Union address, 3 December 1861

Abraham Lincoln proposes setting up a colony of American Blacks in Central America, 14 August 1862

Abraham Lincoln states that he did not fight the Civil War over slavery, 22 August 1862

References:

1. “Speech at Peoria, Illinois” (Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln: volume 2), pp. 255-256

2. Speeches and Debates 1856-1858 (Life and Works of Abraham Lincoln: volume 3), New York: The Current Literature Publishing Co., 1907, pp. 287-289

3. Mrs. Murray Forbes Wittichen, “Let’s Say….”The War Between the States””, United Daughters of the Confederacy (originally published 1 May 1954)

4. “Origins of the American Civil War”, British Library

Martin Kelly, “Top Five Causes of the Civil War: Leading up to Secession and the Civil War”, About.com

“Causes of the Civil War”, History Net

“Causes of the American Civil War”, History Learning Site

5. Francis Lieber (editor), The Martyr’s Monument: Being the Patriotism and Political Wisdom of Abraham Lincoln, as Exhibited in His Speeches, Messages, Orders, and Proclamations, from the Presidential Canvass of 1860 Until His Assassination, April 14, 1865, New York: The American News Company, 1865, pp.88-89

“First Annual Message: December 3, 1861”, The American Presidency Project, University of California, Santa Barbara

6. Letters and Telegrams: Adams to Garrison: Including Messages to Congress, Military Orders, Memoranda, etc., Relating to Individual Persons: By Abraham Lincoln (Life and Works of Abraham Lincoln: volume 8), New York: The Current Literature Publishing Co., 1907, pp. 44-45

7. Francis Lieber (editor), The Martyr’s Monument: Being the Patriotism and Political Wisdom of Abraham Lincoln, as Exhibited in His Speeches, Messages, Orders, and Proclamations, from the Presidential Canvass of 1860 Until His Assassination, April 14, 1865, New York: The American News Company, 1865, pp. 126-131

[For further reading, see the Wikipedia entry: “Abraham Lincoln”]

Speak Your Mind