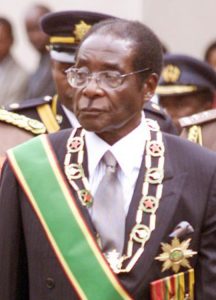

Robert Mugabe, in his role as President of Zimbabwe (wearing not quite as many medals as Idid Amin, but he’s trying)

So, Robert Mugabe has finally died; a disgusting wart upon the blemished face of the earth has fallen off, leaving the world just a little bit cleaner.

Mugabe passed to the realm below on 6 September 2019, at the age of 95; he was a man who was much despised for his organising of terrorist attacks against white farming families in Rhodesia. The blood of innocent men, women, and children were on his hands; although, as a psychopath, Mugabe could care less who, or how many, were murdered during his homicidal bid to gain power.[1]

Mugabe was a full-on Marxist; unlike most of the Cultural Marxists in the West, Mugabe didn’t hide his dedication to Communism and the destruction of the West under the guise of tearing down societal institutions, but instead loudly proclaimed his passion for the murderous ideology from atop the human abattoirs he created. Mugabe became a Marxist whilst he was at university in Ghana (many Western universities are riddled with communist teachers trying to brain wash their students, so it would not be surprising to discover that universities in Africa are similarly afflicted).[2]

However, for much of his dictatorial reign, the bleeding hearts and Leftists of the West said very little of his murderous regime; or, if they did, it was in the vein of “a good man gone wrong” — after all, if they admitted that he was a nasty piece of work right from the start, who they supported, they weren’t going to look too good, especially as it could be said that they were morally complicit for having supported this communist murderer in the first place.

James Kirchick, in the Los Angles Times, noted this style of fawning over Mugabe:

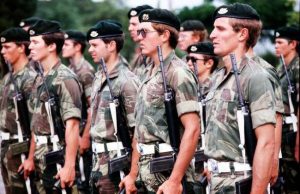

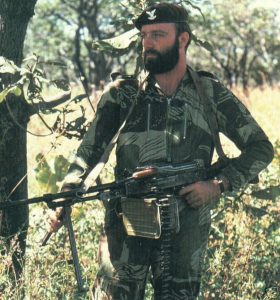

Mugabe and his terrorists“The characterization of Mugabe as a good man gone wrong extends to popular culture as well. … this popular conception of Mugabe — propagated by the liberals who championed him in the 1970s and 1980s — is absolutely wrong. From the beginning of his political career, Mugabe was not just a Marxist but one who repeatedly made clear his intention to run Zimbabwe as an authoritarian, one-party state.

… Mugabe did not “morph” into “a caricature of the African Big Man.” He has been one since he took power in 1980 — and he displayed unmistakable authoritarian traits well before that. Those who were watching at the time should have known what kind of man Mugabe was, and the fact that so many today persist in the contention that Mugabe was a once-benign ruler speaks much about liberal illusions of African nationalism.

… Months after his election in 1980, the New York Times opined that “Mr. Mugabe has quickly established himself as an African statesman of the first rank.” The media already had its villain — Rhodesia’s intractable whites — and portraying Mugabe as just another African strongman bent on turning his country into a one-party dictatorship would have complicated the story of good versus evil.

… Lewis, and everyone else who ever feted Mugabe, was not just proved wrong about the despot “at least over time.” They were wrong the minute they endorsed him.”[3]

Robert Mugabe was a member of the National Democratic Party (NDP), but after the NDP was banned in December 1961, he joined the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), which was led by Joshua Nkomo. However, along with others dissatisfied with Nkomo’s leadership, Mugabe helped to form the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) in 1963 Subsequently, Nkomo reformed ZAPU as the People’s Caretaker Council, although the group was widely still referred to as ZAPU.[4]

Mugabe was jailed in 1964 for subversion, along with many of ZANU’s leadership. However, the ZANU executive was able to smuggle messages outside to their group, by using sympathetic black prison guards, and were therefore able to continue to arrange terrorist outrages against white civilians. Mugabe was released in 1974; he was later elected leader of ZANU.

The ZANU leadership created the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) as a military wing, which carried out attacks against Rhodesia from Mozambique and Zambia. Similarly, ZAPU formed the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA), which operated against Rhodesia from Zambia and Botswana. The terrorists and guerillas of Mugabe’s ZANU were mainly funded and armed by communist China, whilst Nkomo’s ZAPU was primarily backed by communist Russia (although other communist countries were involved as well).

When three black terrorists (James Dhlamini, Victor Mlambo and Duly Shadreck) were convicted in a Rhodesian court, and sentenced to death, Queen Elizabeth II declared that she had commuted their three death sentences to life imprisonment, on the advice of the British government. However, Chief Justice Sir Hugh Beadle of the Rhodesian High Court ruled that the “royal prerogative of mercy” had been transferred to the Rhodesian Executive Council.[5]

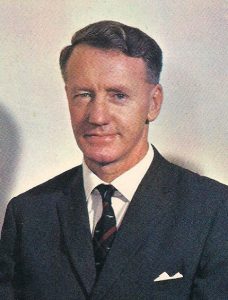

The Unilateral Declaration of IndependenceThe British government wanted Rhodesia to let the blacks rule the country, with “majority rule”. White Rhodesia resisted the ever-increasing political demands from Britain to hand the country over to the blacks, and eventually Rhodesia declared its sovereignty to the world. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Ian Smith, the Rhodesian government signed a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on 11 November 1965.[6]

Subsequently, the United Nations put into place economic sanctions against Rhodesia, an act which indirectly assisted the black revolutionaries. The day after independence had been declared, the United Nations’ Security Council voted to “condemn the unilateral declaration of independence made by a racist minority”, and in the following week it voted to condemn the “the usurpation of power by a racist settler minority”, asking the British government to “to quell this rebellion of the racist minority”, and called upon all countries to “desist from providing it with arms, equipment and military material, and to do their utmost in order to break all economic relations with Southern Rhodesia, including an embargo on oil and petroleum products” (the British continued to call Rhodesia by its historical name of Southern Rhodesia, even though Northern Rhodesia had become independent in 1964 and renamed itself Zambia). Both of these resolutions of the UN Security Council were passed, 10 votes to none, with France abstaining).[7]

The British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson (leader of the Labour Party), declared in the British parliament that the Rhodesian government was an “illegal régime”. Although Wilson decided against an invasion of the rebel state, he was determined to destroy it by other means. The British government and the United Nations engaged in economic warfare against Rhodesia. The British sent a naval squadron to Africa to inspect ships and stop any oil headed for the embattled white nation.[8]

The white Rhodesians attempted to remain friends with the British Commonwealth, but the British government instead insisted that they bring in “majority rule”, which would effectively hand over power to the blacks. However, the Rhodesian whites countered such naive proposals by saying that the blacks weren’t capable of handling such responsibility, pointing to other countries where the blacks had taken over, such as Kenya, where they ruined the country when they took over.

Rather than create a nightmare for their nation, white Rhodesians voted for a new constitution, and the government announced that they were a republic on 2 March 1970.[9]

The reality of “majority rule”Rhodesians knew what “majority rule” meant in Africa. Anthony Peck, a lawyer who had been a left of centre candidate in Rhodesian elections, wrote a letter which was published in The Times (London) in November 1965, in which he said:

“Mr. Wilson’s grandiloquent phrase “majority rule” is a terminological inexactitude masquerading in the purple robes of a Pontius Pilate. Mr. Wilson well knows that in Ghana there is no “majority rule”: one man rules — Dr. Nkrumah; he well knows the position to be the same in numerous other African states; and he well knows that “majority rule” in Rhodesia would today, inevitably, bring dictatorship by one particular man.”[10]

It was all very well for Harold Wilson and the bleeding hearts of the West to demand “majority rule”, as they weren’t the ones who would have to live under the heel of some black dictator; as usual, it wasn’t the bleeding hearts who suffered the consequence of their actions, although — due to their commitment to a multiracialist ideology — they were quite happy to cause tens of thousands of people to die.

Trade with Portugal and Mozambique

South Africa and Portugal continued to trade with Rhodesia. Also, various other countries engaged in under-the-table trade. All of these economic transactions helped Rhodesia to weather the economic storm, and gave the country time to slowly build up its own industries.

However, on 25 April 1974 there was a left-wing military coup in Portugal; subsequently, the new regime signed an agreement in June 1975 to give independence to its colony of Mozambique, thereby swapping the Portuguese-backed government of Mozambique with one run by FRELIMO (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique, or Front for the Liberation of Mozambique), a communist organisation of black guerillas and terrorists, which had previously been at war against the colonial status quo.

With the advent of left-wing regimes in both Portugal and Mozambique, Rhodesia lost a valuable ally and a friendly neighbour, and the Rhodesian communists gained a favourable staging ground for their attacks.[11]

Vorster, Kissinger, the CIA, and the betrayal of RhodesiaIn 1975 and 1976 the US and South African governments began to apply heavy pressure on Ian Smith to agree to “majority rule” (i.e. black rule), with Henry Kissinger, the US Secretary of State, being involved with the talks. The South African government began to downgrade their economic and military aid to Rhodesia; halting fuel supplies going from South Africa into Rhodesia would be a crippling blow. Some believe that the South African Prime Minister, John Vorster, was motivated by furthering the policy of détente with the Black African states, in the belief that distancing SA from Rhodesia would ingratiate them with black Africans.

An alternative hypothesis is that the USA secretly threatened South Africa with economic reprisals unless they dropped their support for Rhodesia. Whilst that would be a matter of speculation, there is evidence to support the hypothesis. In 1975 George H. W. Bush, Director of the CIA (later President of the USA, 1989-1993), sent a secret intelligence memorandum to Henry Kissinger, “Present South African attitudes on the Rhodesian situation” (now declassified), in which he effectively outlined South Africa’s weak points.[12]

Bush noted that “The strongest arguments in favor of a South African disengagement from support of Rhodesia may derive from Pretoria’s concern about its own continuing racial strife, and worries about the South African economy.” He also said that, since the fall of the old Portuguese government in mid-1974, Vorster had already been gently pushing Smith towards a “compromise settlement”, leading to a “moderate, black government within five to ten years”, and “opening an era of collaboration between Pretoria and black governments throughout southern Africa”; although this idea had been “hampered by the gap between the strong pro-Rhodesia attitudes among South African whites and Vorster’s own stated goal.”The CIA director pointed out that “South Africa has provided Rhodesia with substantial economic and military support, which has become increasingly vital for the Smith regime under the cumulative impact of sanctions and insurgency.” As Mozambique had closed its border with Rhodesia in 1974, this meant that South Africa subsequently “handled almost all of Rhodesia’s overseas trade”, as well as buying “significant amounts” of Rhodesian exports. Bush also noted that “South African military aid to Rhodesia … has become critical with the recent expansion of foreign-backed insurgency”, but that there were “affordable limits of South African military aid to Rhodesia”; noting that, following on from black rioting in SA that a “sense of emergency would favor public acceptance of any curtailment of aid to Rhodesia that Vorster presents as essential for internal security.”

Significantly, Bush had mentioned South African fears that “blatant participation in Rhodesian “sanctions busting” would spur new demands for mandatory sanctions against South Africa.” The document also noted that sending troops to help Rhodesia could end up costing SA the “important economic ties” it had maintained in Mozambique, as well as which Vorster appeared to be “especially anxious” to avert an “increased Soviet presence in Mozambique”. The final section in the document points out that the “need to conserve dwindling foreign exchange reserves may become the most persuasive reason — to South Africa — for curtailing military support whenever the Rhodesians are unable to pay … Government leaders have acknowledged that major increases in military expenditure since 1974 are a significant factor in the foreign exchange bind.”It doesn’t take much effort to see the conclusions Kissinger could reach from reading this document: Threaten Vorster with the USA going all-out to promote sanctions against South Africa if he doesn’t, in turn, threaten Smith with curtailing economic and military support for Rhodesia (which would cripple the already struggling country); then use the threats to make Smith agree to a settlement, promising US support for a Rhodesian government led by black moderates (without actually caring if the moderates stayed in power for long or not).

Economic problems and hard choices

The economic troubles hurting Rhodesia, caused by international sanctions, would have been weighing heavily upon Smith. The loss of assistance from Portugal and Mozambique further damaged Rhodesia’s chances of survival. However, if South Africa was to withdraw its economic and military support (as apparently threatened by Vorster, backed up by Kissinger), then the small white republic of Rhodesia would face destruction. Therefore, Ian Smith likely felt that he had no choice but to co-operate with the non-violent black groups, and so agreed (under duress) to arrange new elections, which would include widespread black participation, thus bringing “black majority rule” to the country.[13]

Indeed, not content with trying to destroy Rhodesia economically, the British assisted the black communists by warning Mugabe and Nkomo of assassination attempts planned by the Rhodesians (Ken Flowers, the head of Rhodesian Intelligence, was secretly passing on information to the British); the black leadership was therefore able to continue on as before, ordering incursions and the murder of white farming families.[14]

With Rhodesia being strangled by the hands of the Western liberal democracies, Smith was facing an economic and military nightmare for Rhodesia. He had to make a hard choice, and did so. Subsequently, multiracial elections were arranged for June 1979. As a result of the black-majority vote, Rhodesia was taken over by the blacks and renamed Zimbabwe Rhodesia. However, the new government wasn’t accepted by the violent black communist groups, and it lasted for only a short period (as did the double-barrelled name).

The British orchestrated the Lancaster House Agreement, which resulted in a ceasefire, new multiracial elections, and the appointment of a new British Governor. ZANU won the elections held in March 1980, and Robert Mugabe became Prime Minister. In April 1980, the British government granted independence to the republic of Zimbabwe (which remained within the British Commonwealth as an independent state).

Many people have judged Prime Minister Ian Smith harshly, but he was probably going to be damned no matter what he did. Smith’s basic choices were — 1) to dig in his heels and defend white Rhodesia no matter what, even to the bitter end (if that’s how it panned out); 2) to have a moderate black-run government; or 3) to hand over power to the black communists. Smith chose the moderate option, but — as we can easily see, with the marvellous view afforded to us by standing on the top of Mount Hindsight — that quite quickly led to the communist option anyway.A fourth option, which would have been politically unpopular with many Rhodesians, but had possibilities nonetheless, would have been to publicly declare a desire to merge with South Africa, calling upon pro-Rhodesian South Africans to make sure it happened — that may have been a pie-in-the-sky option, considering the likely strong political opposition to it. However, if it had worked, a much stronger pro-white South Africa would have been the result. It certainly would have been a better choice than giving the country to Mugabe; but, as with all “Hail Mary” political options, it would have been a roll of the dice.

Some say Ian Smith should have fought harder to save Rhodesia, and to ensure the future of the white population, whilst others believe that he had little choice, given the political and economic realities of the situation. Certainly, handing the country over to the blacks did the white population no favours, and many have argued that it would have been better to fight on alone and tough it out, because the alternative was to bring about the death of the nation anyway. Nonetheless, once power was handed over to the blacks, white Rhodesia was finished.

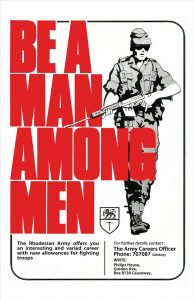

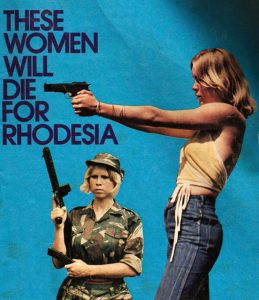

The Rhodesian Army had fought long and hard against Mugabe’s communists, but they were betrayed by the liberal democracies of the West

Mugabe became the virtual dictator of the country. Under his rule, Zimbabwe became infamous for its brutality, corruption, and incompetence — not unlike many other communist countries. White farming families were attacked, prompting many to flee the country. Inflation shot sky-high, and the country became an economic mess.[15]

Mugabe’s Five Brigade was particularly notorious for attacking the political opponents of Mugabe; trained in North Korea, it was “responsible for mass murders, beatings and property burnings in the communal living areas of Northern Matabeleland, where hundreds of thousands of ZAPU supporters lived”. In 1981 the black military unit descended upon Matabeleland like a plague of violent locusts — “Within six weeks, more than 2,000 civilians had died, and thousands were beaten. Most of the dead were killed in public executions. The largest number of dead in a single incident was in Lupane, where 62 men and women were shot on the banks of the Cewale River on 5 March”. In 1983 and 1984 the violence continued — “people were taken from buses at road blocks, and never seen again”; “systematic mass beatings and mass detentions lasted several months”.[16]

In scenes reminiscent of the Soviet Union’s starving of millions of people in the Ukraine, people living in Matabeleland South were subjected to a food embargo by Mugabe in 1984. As Kenneth Good explained in Counter Punch:

Nothing even remotely like this had occurred in white Rhodesia. There was racial discrimination, whereby the whites held most of the voting power, but no mass murders, mass beatings, and mass disappearances. Whilst the British government had sent in the Royal Navy to blockade white Rhodesia, and the UN had tried its best to economically destroy the country — all over “racism” — they did little to nothing when Mugabe was murdering tens of thousands of blacks.“Residents were already affected by three consecutive years of drought, when government restrictions prevented all movements of food into and around the region. Existing drought relief was stopped and stores were closed. Almost no people were allowed into and out of the region to buy food, and private food supplies were destroyed. 5 Brigade ‘actively punished those villagers who shared food with starving neighbours.’ Commanders repeatedly declared at rallies that the government intended to ‘starve all the Ndebele to death’: people were told ‘they would be starved until they ate each other, including their own wives and children.’ To ensure that starvation was absolute, 5 Brigade also broke down fences to allow cattle to graze whatever few hardy crops might have survived.

… Mass detentions and beatings deepened the terror. A common pattern involved making people lie face down in rows, after which they were beaten with thick sticks. People were made to roll in and out of water while being beaten, sometimes naked. Sadism reigned. Men and women were forced to ‘run around in circles with their index fingers on the ground, and were beaten for falling over.’

… Estimates vary, but perhaps 20,000 were killed by the time 5 Brigade withdrew in 1986. ‘Probably ‘hundreds of thousands of others were tortured, assaulted or raped or had their property destroyed’. Danny Stannard, a member of Rhodesian security and of the CIO, believes that ‘anything between 30 and 50 thousand died’.

… Britain was largely unconcerned by events in Matabeland.”[17]

Where were the economic sanctions against black Zimbabwe? There were none, because Robert Mugabe was the beneficiary of “black privilege”, whereby you can get away with murder because of the colour of your skin. If the white Rhodesians had acted as Mugabe did, not only would they have copped economic sanctions, but it would be more than likely that the United Nations would have told some pliant “bleeding heart” Western nations to invade the country; but, because Mugabe was black, he could get away with it.

Indeed, as The Times and The Week reported,

“Britain adopted a policy of “wilful blindness” towards atrocities carried out by Robert Mugabe’s army in Zimbabwe in 1983, research has claimed. The UK government engaged in a “conspiracy of silence” while thousands of civilians were massacred in Matabeleland”.[18]

“Thousands of documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act show that British officials in London and Zimbabwe knew of the atrocities but sought to minimise their scale”.[19]

As Graeme Wood wrote in The Atlantic,

“The international community was content to ignore the mass violence against blacks”.[20]

However, it wasn’t just the blacks who were on the receiving end of Mugabe’s hatred. He had decided that the white population was too rich, and it was time to take them down a peg or two by stealing their farms. Kenneth Good wrote:

“By early 1994, the government operated a so-called land redistribution programme which, according to Robert Drew, was ‘benefiting a powerful new elite’, specifically senior officers in the Army, Air Force, Police, and the CIO … The invasion of commercial farms commenced … spearheaded by self-styled War Veterans. Numbering between 50,000 and 70,000, they had been organised and promoted by the President. … By mid-March, more than 500 farms had been occupied, and by November, 1,700 had been seized

… On the 20th anniversary of the country’s independence, President Mugabe branded white commercial farmers “enemies of the state”. As assaults on farmers and farm workers, and deaths, escalated from April 2000, judicial orders for the removal of occupiers were ignored by the police.

… The losses experienced in the land seizures were enormous and many. As detailed by the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum in their report of June 2007, ‘widespread human rights violations were inflicted upon white farmers and black farm workers by agents of [Mugabe’s government]’ during the invasions from 2000 to 2005. ‘Immense financial losses were inflicted upon the farm owners’, and farm workers suffered ‘catastrophic losses of income, habitation, health services and access to clean water and sanitation, contribut[ing] to a high death rate.’ 53,000 people suffered ‘assaults, torture, being held hostage, unlawful detention and death threats’, their survey showed. If extrapolated to include all commercial farms nation-wide, the number of people suffering abuses during the seizures ‘could be more than one million’.

… The Forum found no evidence of spontaneous, popular seizures, as government repeatedly claimed, but instead planned and organised expropriations by state agents.

By the end of 2005, close to 4,000 of the original 4,500 commercial farmers had been evicted from their farms, and ‘hundreds of thousands of farm workers had lost their jobs and their homes’.[18] The NGO Forum’s report of April 2010 (Land Reform and Property Rights in Zimbabwe), noted that over the then eight years of violence, 1.3 million workers and their families had been displaced from their homes.

… The 2010 report also noted that for many years, Zimbabwe had been a bread basket of Africa. With productive farmland, it grew enough food to feed its own people and export the rest. Now it was ‘dependent upon food aid programmes to feed its population.’”[21]

The corruption and violence went on and on and on. Police were paid off, judges were bribed, elections were rigged, and people continued to die. The result of handing power over to the blacks was pretty much what the white Rhodesians had predicted.

The end draws near for MugabeMugabe sent the country’s economy into a nosedive. Graeme Wood was critical of his leadership:

“After the genocide in Matabeleland, he turned against white Zimbabweans, sanctioning a grisly demagogue, Chenjerai Hunzvi, to whip up vigilante fervor against white farmers. (Hunzvi called himself “Hitler” and “Zimbabwe’s biggest terrorist.”) The Zimbabwean agricultural industry, the country’s largest earner of foreign currency, collapsed, and by the late 1990s Mugabe began resorting to mass-printing of currency to make budget.”[22]

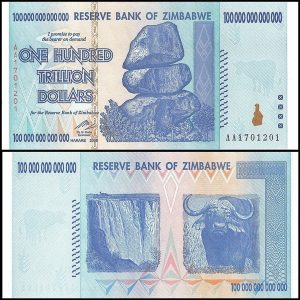

Mugabe’s rule had an enormously negative impact upon the black population. Not only did they have to contend with violence from Mugabe’s communist one party state, they had to live with the country’s economic mismanagement and corruption, as well as deal with a lowered food production rate, due to white farming families being attacked, farmers having their land forcibly taken over by blacks (with varying degrees of competence, or lack thereof), and other farmers fleeing the country. Stephen Talbot, series editor of the 2006 PBS documentary “Zimbabwe: Shadows and Lies”, said that life expectancy in the country had “declined in the last two decades from 62 years to a mere 38 years”. By 2007 Zimbabwe’s official inflation rate was over 7,600%, although independent sources estimated that the real inflation rate was about 25,000%. Things got so bad that people in Zimbabwe were eating their pets for food.[23]

Zimbabwe’s economy got so bad that the currency became almost worthless. The country even made the record books by printing the world’s highest denomination note — with a face value of 100 trillion dollars. By April 2009, things had gotten so bad that the country ended up using currencies from all over the world instead of their own — including the Australian dollar, Botswana pula, British pound sterling, Chinese yuan, the euro, Indian rupee, Japanese yen, South African rand, and the United States dollar (the Zimbabwean dollar was demonetised in 2015, and a new Zimbabwean currency was introduced in June 2019). By 2009, hyperinflation had reached 500 billion per cent, which was probably another world record.[24]

Mugabe deposed

In the end, President Mugabe went one step too far when he tried to set up his wife in the country’s second-highest position (and therefore as his successor), by using her to replace Vice-President Mnangagwa. His wife, Grace, was widely hated, and so the Army stepped in and deposed Mugabe in a bloodless coup in November 2017. After some political wrangling, he resigned.

Despite some weak attempts to declare his removal illegal, Mugabe gave up and moved on. He didn’t have much to complain about, as — in an attempt to keep the peace — he had been given a small mansion, $10 million, a staff, and was allowed to keep all of his misbegotten loot which he had accumulated during his despotic decades. As far as coups go, he had a very easy ride.[25]

The corruption created by Robert Mugabe stank to high heaven; leaked diplomatic cables estimated that his family’s wealth to be over one billion dollars.[26]

Death of a dangerous dictatorFollowing on from some health problems, Mugabe passed away at Gleneagles Hospital, in Singapore, on 6 September 2019.

Mugabe’s one big achievement in life was to rule Zimbabwe, which he made a complete mess of — unless the situation is seen from his point of view; after all, he had skimmed billions from the riches of the country, and then walked away with no consequences. The man should have been sentenced to jail for life, if not shot.

Ian Smith’s prophecy was proven to be correct. In an televised speech, broadcast on 20 March 1976, Smith had warned:

“I don’t believe in majority rule ever in Rhodesia …not in 1,000 years. I repeat that I believe in blacks and whites working together. If one day it is white and the next day black, I believe we have failed and it will be a disaster for Rhodesia.”[27]

As predicted by many (not just by Ian Smith), black rule for Rhodesia/Zimbabwe had turned out to be an utter disaster.

Robert Mugabe is dead, but his legacy of destruction lives on in a country which was once financially successful, but is now an economic mess. Under white rule, Rhodesia provided economic stability to both black and white citizens. The anti-Rhodesians, rather than improve matters, brought about death and destruction.

However, it should be remembered that Mugabe was merely a conduit for what happened to Rhodesia. The main reason that the country gave in was because it was betrayed by fellow whites — the useful idiots of the Western democracies and the United Nations. If Rhodesia hadn’t been betrayed by the leaders of Great Britain, the USA, South Africa, and various other countries, it could have stood for ever. The bleeding hearts of the West achieved their dream, and destroyed a once-prosperous nation.

References:

[1] Robert Mugabe, tyrant of Zimbabwe who presided over the despoliation of the country once hailed as the ‘jewel of Africa’ – obituary, The Telegraph, 6 September 2019

[2] Stephen Talbot, From liberator to tyrant: Recollections of Robert Mugabe, PBS, 2006

[3] James Kirchick, Mugabe: a tyrant from the start, Los Angles Times, 30 September 2007

[4] Robert Mugabe fast facts, CNN, 8 September 2019

Robert Gabriel Mugabe, South African History Online

[5] The two faces of murder in Rhodesia — black and white (Salient, Victoria University of Wellington Student’s Newspaper, Volume 31, Number 5, April 2 1968), Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand)

The question of Rhodesia, Mrs Jones and Me: Runcible Spoon Adventures, 11 November 2016

‘It all began in Byo’, The Sunday Mail, 9 June 2019 [Norman Makotsi reports that Nesbert Makotsi had admitted to killing a white Rhodesian, as part of a group which included Dhlamini, Mlambo, and Shadreck]

[6] 1965: Rhodesia breaks from UK (On this day, 11 November), BBC

Modern History Sourcebook: Rhodesia: Unilateral Declaration of Independence Documents, 1965, Fordham University (New York)

[7] Resolution 216: Southern Rhodesia: Abstract: Resolution 216 (1965) of 12 November 1965, United Nations Security Council Resolutions

Resolution 217: Southern Rhodesia: AbstractResolution 217 (1965) of 20 November 1965, United Nations Security Council Resolutions

On this day: Rhodesia declares itself a republic, Finding Dulcinea, 2 March 2011

[8] Rhodesia: HC Deb, 20 December 1966, vol 738, cc1175-83, UK Parliament

On board the Tiger, Rhodesia and South Africa: Military History

John Rentoul, Wilson mooted plan to invade Rhodesia, The Irish Times, 2 January 1996

[9] 1970s: Memories of Rhodesia (On this day, 2 March), BBC

[10] A letter from a Rhodesian lawyer, A.J.A. Peck, published in the Times of London on the 19th November, 1965, Window on Rhodesia – the Jewel of Africa

See also: Some recommended reading, Window on Rhodesia – the Jewel of Africa [see section re. A.J.A. Peck]

[11] History of Portugal, Portugal.com

Revolution in Portugal, Socialism Today, issue 82, April 2004

The New State after Salazar, Encyclopædia Britannica

See also: Carnation Revolution, Wikipedia

FRELIMO [Frente de Libertação de Moçambique; Front for the Liberation of Mozambique], Wikipedia

[12] George Bush, Present South African attitudes on the Rhodesian situation, Central Intelligence Agency, 31 August 1975 [marked “Secret/Sensitive”; declassified 23 September 2010, code: LOC-HAK-91-6-31-0] (see “key points” and sections 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 15, 19-21, 22)

[13] 1976: White rule in Rhodesia to end (On this day, 24 September), BBC

[14] Mike Thomson, Did UK warn Mugabe and Nkomo about assassination attempts?, BBC News, 1 August 2011

[15] Angus McDowall, Zimbabwe: Death toll rises in Robert Mugabe’s reign of terror before election, The Telegraph, 21 June 2008

Anatomy of terror, Window on Rhodesia – the Jewel of Africa

Edwin Mora, 5 Horrors of Late Dictator Mugabe’s Legacy in Zimbabwe, Breitbart, 6 September 2019

[16] Kenneth Good, The brutality of Robert Mugabe and Zanu-Pf in Zimbabwe, Counter Punch, 10 September 2019

Nightmare of Mugabe’s Matabele atrocities, Mail & Guardian, 2 May 1997

Gukurahundi report: A lot to hide in Matabeleland atrocities, The Zimbabwe News, 4 February 2016

[17] Kenneth Good, The Brutality of Robert Mugabe and Zanu-Pf in Zimbabwe, Counter Punch, 10 September 2019

[18] Lucinda Cameron, Britain ‘turned blind eye’ to Mugabe army unit atrocities, The Times, 26 April 2017

[19] UK downplayed Robert Mugabe massacre in Zimbabwe: Officials in London accused of ignoring massacre of thousands of dissidents throughout the 1980s, The Week, 18 May 2017

[20] Graeme Wood, Robert Mugabe died too late: His rule began brutally and ended in pathetic squalor, The Atlantic, 7 September 2019

[21] Kenneth Good, The Brutality of Robert Mugabe and Zanu-Pf in Zimbabwe, Counter Punch, 10 September 2019

[22] Graeme Wood, Robert Mugabe died too late: His rule began brutally and ended in pathetic squalor, The Atlantic, 7 September 2019

[23] Stephen Talbot, From liberator to tyrant: Recollections of Robert Mugabe, PBS, 2006

Angus Shaw, Pets killed for food in Zimbabwe, Breitbart, 14 September 2007 [archived]

Angus Shaw, Pets slaughtered in meat-starved Zim, Mail & Guardian, 14 September 2007 [The M&G article is essentially the same as the Breitbart article, although it does not have the paragraph which says “Mugabe’s critics say corruption and his stewardship of the economy have led to the crisis. They point to the often-violent, government seizures of thousands of white-owned commercial farms that began in 2000 and disrupted the agriculture-based economy in what was once a regional breadbasket.”]

Pets being eaten in Zimbabwe, Jammie Wearing Fool, 14 September 2007

[24] Robert Mugabe: Ruthless tyrant who presided over bloodshed and persecution, The Irish Times, 20 November 2017 [hyperinflation of 500 billion per cent]

Earl Nurse, The 100 trillion dollar bank note that is nearly worthless, CNN, 6 May 2016

[25] Mark Duell, Is ‘Gucci’ Grace Mugabe heading back to Zimbabwe to face the music? Dictator’s widow hides under a blanket outside funeral home Singapore as she faces arrest for stealing the African country’s wealth, Daily Mail, 6 September 2019

[26] Mark Duell, Is ‘Gucci’ Grace Mugabe heading back to Zimbabwe to face the music?, op. cit.

[27] Ian Smith – he was right!, Rhodesia and South Africa: Military History

Further reading:

The life and times of Robert Mugabe, The Zimbabwe Independent, 13 September 2019

Samantha Power, How to kill a country: Turning a breadbasket into a basket case in ten easy steps — the Robert Mugabe way, The Atlantic, December 2003

Katherine Haddon, Margaret Thatcher blocked talks with ‘terrorist’ Mugabe, Mail & Guardian, 30 Dec 2009

Rupert Cornwell, A life in focus: Ian Smith – last white leader of Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, who fought to preserve minority rule, The Independent, 2 February 2019 [an anti-white, anti-Ian Smith diatribe]

Ian Smith the last White leader of Rhodesia disappears into a crack in the sky at 88, David Duke, 23 November 2007

Authentic 100 Trillion banknotes: Latest on counterfeit 100 trillion notes and novelties, 100trillions.com

A timeline of conservation and wildlife management in Zimbabwe, Zim Conservation, [2005?] [archived]

See also:

Rhodesia, Wikipedia

Robert Mugabe, Wikipedia

Zimbabwe African National Union, Wikipedia

Joshua Nkomo, Wikipedia

Zimbabwe African People’s Union, Wikipedia

Gukurahundi, Wikipedia

Ian Smith, Wikipedia

Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence, Wikipedia

Unilateral Declaration of Independence, Wikipedia

United Nations Security Council Resolution 216, Wikipedia

United Nations Security Council Resolution 217, Wikipedia

John Vorster, Wikipedia [Balthazar Johannes Vorster; known as “B. J.”; since the 1970s, known as “John”]

Internal Settlement, Wikipedia

Lancaster House Agreement, Wikipedia

Zimbabwean dollar, Wikipedia

Speak Your Mind